Noir Press: Bringing Lithuanian Prose to the English-Speaking World

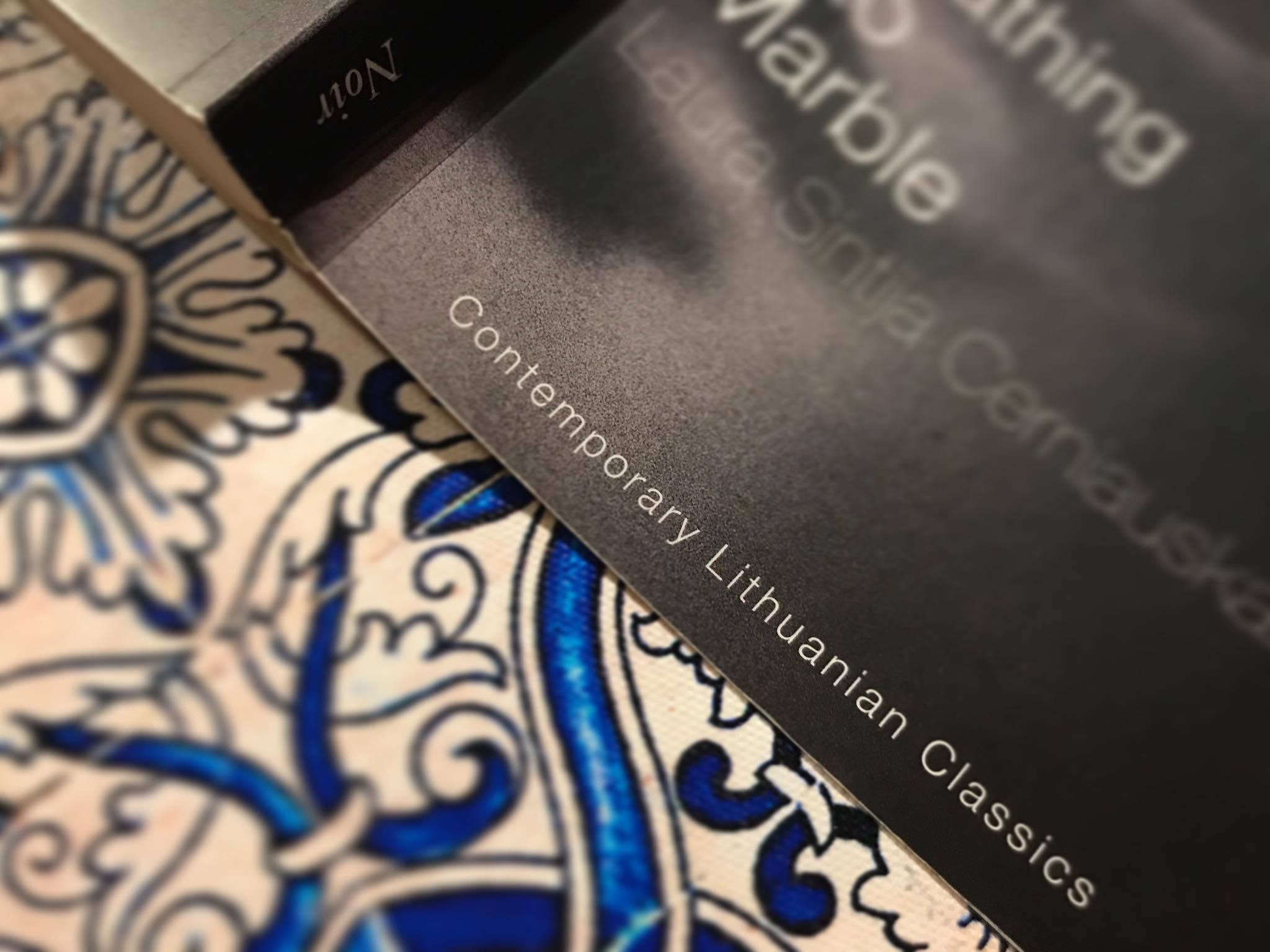

Literature in translation offers a bridge to different cultures, which is why Noir Press, a small independent publishing house based in the UK, is doing its bit as a cultural envoy for Lithuania. Noir Press exclusively publishes contemporary Lithuanian novels, making the rich literature from this small Baltic country accessible to the English-speaking community. Panel has been fortunate enough to have formed a good relationship with Noir Press. We've published reviews of Noir Press books such as Breathing Into Marble by Laura Sintija Cerniauskaite in issue 1 and Devilspel by Grigory Kanovich in issue 4, as well as an extract from Jaroslavas Melnikas's The Last Day in issue 2, along with an interview with the author. However, we wanted to know more about Noir Press, its story, and more about its founder, Stephan Collishaw.

Jennifer Walker talked Stephan at length about Noir Press, Lithuanian writers, Lithuania's literary scene, and of course, his work as a writer himself.

How did Noir Press begin? What's your story as a publisher?

How did Noir Press begin? What's your story as a publisher?

Frustration, more than anything, gave birth to Noir Press. I've been going to Lithuania since 1995 and have seen the country grow and evolve over the years. Like any other visitor, I have always been keen to read books that come from the region. Books open up the imaginative landscape that accompanies the physical one, and you don't really feel that you can know a place, unless you have been able to access its literature.

Unfortunately, there has been almost no Lithuanian fiction translated into English.

Poetry has been moderately well served, and has been since Soviet times. So, it's possible to read Donelaitis' The Seasons, or (wonderfully) to access many of the poems of Tomas Venclova. But not so its contemporary novelists.

Back in 2015, when I started thinking about the idea, there was no full length contemporary Lithuanian novel published in English in the UK. In my desperate search for the translated Lithuanian novel, I scoured every bookshop in Vilnius and was invariably offered three books (all fine works in their own way), one a collection of short stories, the second a travelogue and the third a novel written in English by a Lithuanian American.

So, it was an attempt to somehow rectify that problem, that we eventually ended up establishing Noir Press.

You, yourself don't come from a Lithuanian background, what drew you to the country?

It was a complete accident. I had been planning to start my MPhil in Elizabethan Working Class Fiction at Goldsmiths University. The summer before term started, I went travelling in Eastern Europe with an old friend. We had a minibus and we drove from Warsaw all the way down to Skopje and into Albania. It was one of those incredible experiences that you have in life. I slept in a wooden box on the roof of the van and it was wonderful to wake up in the back streets of Krakow, or in Timisoara (a little unfriendly in 1995, someone threw stones at our van).

Every day my friend would badger me to go and live in an apartment that he had bought in Vilnius. Obviously, I told him I couldn't. I had my course starting. I had a flat in London. But, wandering around Eastern Europe fascinated me. I remember walking through one of those monumentally brutal Soviet housing estates in Poland, gazing through windows, catching glimpses of life inside and wondering, what must it be like to live here?

On our final day, in a scruffy little cafe somewhere in Poland, something just clicked in my head and I thought, 'Why not?' So, I went home to England, deferred my MPhil and got on a bus to Vilnius.

I had no idea where Lithuania was, really. I knew nothing about it at all. That was September 1995. The weather was glorious; what the Lithuanians call a Bobu vasara – an Old Hag's summer (or an Indian Summer, as we say in England).

However, as I recall, 1995 was a difficult year in Lithuania.

Two of the banks collapsed, almost bringing down the government. Violent crime was high (the previous year they had had their last, hurried state execution, dispatching the head of the Vilnius Brigade, while parliament discussed abolishing capital punishment, so concerned were they by the rise in organised crime). There was a diphtheria outbreak in Vilnius. In November it started to snow, and it didn't really let up until March. Cars disappeared under snow drifts. Temperatures plummeted to -28. And I spent my time wandering the streets of the city and I absolutely fell in love. With the city. With the place. With the vitality and energy and creativity of the people.

How did you find learning Lithuanian? Did you find you reached a level that allowed you to dip into Lithuanian literature?

My progress in Lithuanian has been slow and fraught. I'm not a natural linguist. I got married at the end of my year in Lithuania and inherited two lovely Lithuanian stepdaughters who spoke very little English. So, to begin, with my progress was fairly rapid, but it consisted of phrases like, Don't pick your nose, or Could you take your feet off the table while we're eating? However, the girls picked up English much quicker than I picked up Lithuanian, being much clever than I, and so it slowed down again.

My wife has been fairly instrumental in helping to improve my language skills, but she is a fairly brutal teacher and I'm a fairly sensitive student. I once wrote her a poem in Lithuanian. She literally rolled around the floor laughing when she read it. Then she phoned her cousin and they laughed together. So, you see, it's been a difficult journey.

I do now read Lithuanian; I try to ensure that every other novel I read is in Lithuanian. So far, I've been reading western thrillers translated into Lithuanian as they have been easier for me to follow, but I'm making a concerted effort to ensure that I'm reading Lithuanian novels written by Lithuanians now.

You lived in Vilnius for a while, did you have the chance to immerse yourself in the local literary scene, how did you find it?

When I went to Lithuania, I had a half-written novel stuffed in my backpack. It was my intention to spend the year focused on finishing it off. However, I hardly wrote a word while I was there. Life was far too interesting to be spending it locked away in a room with a typewriter – there were cafes to drink coffee in, narrow lanes to explore, I learned to dance at evening classes run by the famous Lithuanian dance teacher Tomas Petreikis.

I certainly would not have felt comfortable mixing with the literary world at that point in time.

Even after my first novel was published in 2003, and I was living off my advance and writing my second novel, I still never felt comfortable calling myself a writer. And I've never really mixed with other writers.

Starting the press has allowed me to get to know some of Lithuania's writers and that has been a real pleasure. They have been incredibly generous and humble and thoughtful. I'm always amazed at the vibrancy of the Lithuanian writing scene. They have a number of exceptionally well-attended literature festivals and books fairs and they are not solely focused on the capital.

I'm still very star-struck when I meet these great writers. Highlights for me have included meeting Indre Valantinaite, who is a wonderfully talented poet (I would love to see a collection of her poems released in English), the philosopher Leonidas Donskis, who sadly died way too young, Jaroslavas Melnikas, who we publish in English – he's an enormously talented writer, whose creative, speculative writing deserves much wider acclaim than that which it currently has.

What is it about Lithuanian literature that you find especially compelling?

Lithuanian fiction is fascinating in that, despite it being such a small country, and it not having a long literary tradition, there is enormous variety in the writing emerging from the country. The three giants of the late Soviet period were Jurgis Kuncinas, Ricardas Gavelis and Jurga Ivanauskaite. Quite a few of their novels are available in English now, particularly Gavelis and Kuncinas. Their writing was philosophical, experimental, playful and bohemian and, in Ivanauskaite's case, with a heady dose of Eastern spirituality thrown in.

Today, I think, there is a wider range of voices emerging and they can be very different. There is the beautiful, light quirkiness of the writing of Rasa Askinyte, which is totally different to the very masculine writing of Sigitas Parulskis (his Darkness and Company is available in English from Peter Owen). Laura Sintija Cerniauskaite's darkly poetic voice is very different to the humour of Mark Zingeris.

Another writer who is well worth reading and has been translated into English is Alvydas Slepikas, whose novel In the Shadow of Wolves (Oneworld publications) tells the story of starving Prussian children kicked out from their homes by advancing Russian forces.

One thing that seems to be a unifying theme of Lithuanian fiction is its darkness. You particularly note that in the women writers that we have published. Even a light, laugh-out-loud funny novel like Rasa Askinyte's The Easiest is a novel where you feel the lightness like a skater on thin ice, with dark, freezing water millimeters below.

What is interesting, is that there has not been a great interest in crime fiction in Lithuania: interesting because of its geographical closeness to Scandinavia and also because of the dark tone of its writing generally. I seem to recall one Lithuanian translator explaining that she thought Lithuanians didn't write crime fiction, because in order to write it you have to believe that right will win in the end. That, I think, perfectly summarises Lithuanians. It is perhaps not surprising that the country has the highest suicide rate in Europe.

Noir Press is a really interesting publisher, and I feel fortunate to have read many of the books you've published, how do you pick the books to translate and publish?

Do writers approach you, or is it translators, or do you have a book in Lithuanian you feel must be translated into English?

Each novel that we have published has had its own story. Some of the books have been passionate projects. That was certainly the case with The Last Day by Jaroslavas Melnikas which Marija read and absolutely demanded that we seek the rights for. She was blown away by the skewered way that Melnikas views the world. The Kanovich novels have been a long time coming. I first started talking to the author's son very soon after we had established the press. In many cases, I simply do not understand why these novels have not been published in English before, they're so beautifully written and so important.

One of your missions with Noir Press is to get English-speaking audiences to recognise contemporary Lithuanian literature, and with the recent critical acclaim for Grigory Kanovich's Devilspel--which also won the EBRD prize--that conversation seems to be taking place.

Do you feel that there is an increasing interest in Lithuanian literature in the international publishing world?

I don't think we should try to pretend that there has been some massive resurgence of interest in translated fiction, though book sales of translated fiction have been rising in the UK, they still only account for about 3% of the market. This figure is more depressing still when you drill down into it, because a lot of that 3% is made up of Scandi crime novels (writers like Henning Mankell and Stieg Larsson) and the works of Elena Ferrante.

However, I think that is the reason why small presses and indie publishers are so important. The big five publishers are growing more and more conservative in what they are willing to publish and at a time when the world is crying out to hear a diversity of voices the mainstream publishers are sadly failing us.

Small presses and Indies are publishing some of the most exciting fiction today, and that includes Black writers and fiction in translation. Readers should consider buying books directly from small presses rather than through Amazon or large book chains, as it pumps money into a business that will allow it to carry on publishing these more marginal voices.

I'm really pleased that it is now possible to buy a range of exciting Lithuanian novelists in translation into English and I'm pleased that Noir Press has been a part of that story.

It's quite an achievement to have published books that have received such great reception. How do you think that happened?

It's quite an achievement to have published books that have received such great reception. How do you think that happened?

Obviously, the writing is solid, but as a publisher was there any challenges to get people interested in Lithuanian literature in translation?

I have been enormously grateful for the generous support that we have received over the last few years, whether that was from the Lithuanian Culture Fund, from reviewers and bloggers, or from magazine editors. Each of them has allowed us to promote the novels we have published to a wider readership.

Publishing literature in translation has the added difficulty of it being more difficult to promote because you do not have such ready access to the writer, which is such an important part of the writing and reading industry today.

As a writer myself, I work with my publisher and independently to get myself in front of a live audience or on the radio as often as possible. You understand, as a writer, that people can't buy your book if they've never heard of it.

That is more problematic in publishing translated fiction as bringing a writer over to the UK is both expensive and time consuming for the writer. We really enjoyed bringing Melnikas over to England and doing a number of great readings with him, both in London and at the Lowdham literature festival.

When we publish a book, we have always tried to do something creative to launch it, even if we can't have the author over. In Kanovich's case, Grigory is now too old to be travelling the world doing book tours, but we had a wonderful event in London with Yiddish music and writers talking about his work. We were able to celebrate his 90th birthday and got a personal greeting from the Prime Minister of Lithuania.

Although Noir Press's focus is on contemporary writers who are still alive, are there any Lithuanian classics you would recommend in translation for English readers?

There are many issues to the remit which we set ourselves when we established Noir Press. Our establishing principles were that our writers should be Lithuanian, living and notable. Almost immediately, we were confronted with the problem of what do you mean by Lithuanian? I'm very proud that Lithuanians themselves are pretty elastic around what is considered to be a Lithuanian writer, and always have been. The 18th-century poet Adam Mickiewicz is happily claimed as Adomas Mickevicius. The great Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz described himself as 'the last citizen of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania' and Lithuanians are happy to embrace that. So we publish Grigory Kanovich a Jewish Lithuanian, born in Lithuania, living in Israel, who writes in Russian and Jaroslavas Melnikas, born in Ukraine, but now living and writing in Lithuanian (as well as Ukrainian).

In terms of some of the classic Lithuanian novels that you can find translated into English, I have already mentioned some, but a potted list would include: White Shroud by Antanas Skema published by Vagabond Voices. This is a post-war Lithuanian emigre classic. It tells the story of a Lithuanian refugee at the end of World War Two, who ends up in New York. Vilnius Poker by Ricardas Gavelis published by Open Letter Books. This one is considered the Soviet Lithuanian classic. It depicts a man spiralling into insanity and was considered shocking on publication due to the graphic sexual violence in it. Tula by Jurgis Kuncinas published by Pica Pica Press (who are worth visiting if you're interesting in exploring Lithuanian writing).

Do you have any writers on your radar you'd love to see published? Are there any exciting books in the pipeline coming soon?

Perhaps one of the most famous Lithuanian writers who has not been translated into English is the historical novelist Kristina Sabaliauskaite. Her Silva Rerum series has been a huge success in both Lithuania and Poland and it's a real shame that it has not made its way into English yet.

I'm really excited by the new novel we have just out this summer, Diary of a Jewish Girl by Saulius Saltenis. Saltenis is one of Lithuania's grand old men of writing. His novella Nutbread was one of the great Soviet Lithuanian classics. His writing is very cinematographic, with beautiful set pieces and lovely writing. The new novel tells the story of Esther Levinson, a young Jewish girl who crawls from a mass grave and seeks shelter in the house of a newly married couple. It's a story of resurrection, survival and love. Obsessive love.

You're a writer yourself, can you tell me a little about the books you write? Do you have anything that's come out recently or is coming out?

I write historical fiction and most of my novels have been based in Eastern Europe. My two most recent novels were The Song of the Stork and A Child Called Happiness.

The Song of the Stork is a coming of age tale. Yael, a young Jewish girl, narrowly escapes the liquidation of her small town by the Nazis. She escapes and seeks shelter with a local farmer, known locally as the meshuggener – the village idiot. Aleksas is mute. As the winter snows cut them off on Aleksas' remote farm, a delicate relationship develops between them. It's a novel about a young girl finding her voice at a time in history when a whole community was having their story erased.

A Child Called Happiness is set in Zimbabwe. I've been wanting to write this novel since I went to the country back in 1989. Zimbabwe is a gorgeously beautiful country and it made a great impression on me. The novel follows two stories. In the early 21st century an English girl gets caught up in the land-redistribution when her uncle's farm is surrounded by the notorious War Veterans. The other story traces the history of Tafara starting in the 1890s as white farmers first start moving into the Mazowe valley where he lives.

Leave a Reply