Book Reviews

Chronicles of the Baltics (Issue #1)

Within Memories and Dreams (Issue #2)

Losing Venice (Issue #3)

Concert at a Railway Station (Issue #3)

Times of Turbulence (Issue #4)

Chronicles of the Baltics (Issue #1)

Jennifer Walker

Haunted by the ghosts of Communists past, the former Soviet states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania are countries that have been reborn into new, shifting identities under the blanket of the European Union. Although Estonia shares more in common linguistically with Finland than its Balto-Slavic neighbors to the south, all three of these countries share strong cultural and historical links with one another. Their mutual history with Soviet Russia, which grabbed the territories and incorporated the Baltics into the “Motherland”, has influenced the Baltic States in more ways than one. Within contemporary Baltic literature national identity and a sense of home have become prevalent themes. Begin the Baltic literary exploration with these three translated work authors originating from Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Estonia: The Cavemen Chronicle, Mihkel Mutt (2012)

Estonia: The Cavemen Chronicle, Mihkel Mutt (2012)

Translated by Adam Cullen (2015)

In a country changing over regimes, Mutt’s novel may chronicle a basement bar that lies beneath Tallinn’s medieval streets, but it’s a story of a country and its shifting identity. Told through a series of vignettes about the residents who call the “Cave” their home, an eclectic mix of intelligentsia, artists, and undercover KGB artists, the Caveman Chronicles weaves the reader through a personal history of Tallinn’s creative class and how the shift in regime affects their lives. Some benefit from Estonia’s liberation from the Soviets, others suffer having enjoyed the benefits of the regime. The narrator of the story, perhaps slightly autobiographical, is a tabloid columnist who is a keen observer of the various personalities that walk in and out of his life and the bohemian circle gathering in the Cave, and tries to save fading artistic figures in the post-communist world by promoting them in paparazzi photos used in gossip columns. A fascinating insight into the world of changing Estonia and its cultural undercurrents.

Latvia: Flesh-Colored Dominos, Zigmunds Skujinš (1999)

Latvia: Flesh-Colored Dominos, Zigmunds Skujinš (1999)

Translated by Kaija Straumanis (2014)

This is one of the few pieces of Latvian literature that has made it into English translation. It’s a unique piece of magical realism that presents an alternate history of Latvia. Themes of identity prevail throughout the novel, which is told in two stories - one set in the 18th century and another around World War II. Even if more than a century separates the family residing in a Latvian town that has survived multiple occupations from the Russians and German, the novel reconciles the two threads into one. In the 18th century, Baroness Valtraute von Br?gen’s husband returns: except only half of him. The baron’s body has been severed in two. His lower half sewn onto the body of Captain Ulste, who returns to the baroness and they conceive a child. However, when her husband eventually returns in one piece, questions arise. During World War II, the narrator is a nameless young boy and his half-Japanese step-brother, J?nis, raised by his grandfather The novel dances around the theme of identity - especially national identity and whether nationality is determined by blood, especially in the case of J?nis, who is treated as a foreigner for his Asian appearance, yet identifies with being Latvian andalso Baltic German at the height of World War II’s anti-German sentiment. Zigmunds Skuji?š was one of Latvia’s most renowned writers, and this translation gives English speakers the opportunity to delve into his work.

Lithuania: Breathing Into Marble, Laura Sintija Cerniauskaite (2008)

Lithuania: Breathing Into Marble, Laura Sintija Cerniauskaite (2008)

Translated by Marija Marcinkute (2016)

Breathing Into Marble is a high-octane family drama set in rural Lithuania. Isabel, a young woman living with her husband Liudas and epileptic son Gailius, decides to adopt troubled orphan Ilya on impulse. Ilya doesn’t complete the family the way Isabel had wished. Instead he begins to unravel a thread that leads to tragedy. Uncomfortable memories of the past and the horrors of the present interplay among wild emotions and haunting imagery where the concept of home is torn to shreds. The novel tackles issues from childhood sexual abuse, suicide, and the problems that can arise from the adoption process in Lithuania. The relationship between Ilya and Isabel is at the heart of this story, a moving and intense walk through a dark and twisted relationship. Breathing Into Marble was one of the first novels to be translated from Lithuanian into English.

Within Memories and Dreams (Issue # 2)

Aetherial Worlds

Aetherial Worlds

Stories by Tatyana Tolstaya. Translated by Anya Migdal. Knopf, 2018

Tatyana Tolstaya comes from a famous Leningrad family (her grandparents were literati and her father was an eminent physicist). She has been writing fiction since the early 1980s and almost immediately gained critical acclaim and readership. Later, Tolstaya moved to the USA where she worked as a professor of Russian literature and creative writing, and contributed to the local press. Today, Tolstaya lives in Moscow. She continues to write, blog, teach and travel.

Her newest collection of short stories is written in the first person and inspired by a wide variety of real-life events: buying a new house, meeting an old friend, driving in the dark, cooking kholodets, shopping, entering an apartment which has been sitting abandoned for years. But this constitutes only the first layer, only one entrance to the aetherial worlds where memories live, where small routine coincidences develop into life altering events, where old flats are inhabited by house elves and have doors that lead to parallel dimensions. These worlds are imaginative but not imaginary. Tolstaya plays masterfully with time, has a brilliant gift for dialog and possesses a sharp eye for detail (not to mention sharp tongue). She is simultaneously tender and keenly eager to hear what the world has to tell her.

As the collection unfolds, we see how time accelerates: themes change, places are tranformed, and childhood becomes increasingly remote. Most importantly, the door that connects these worlds remains stalwartly in place.

The Symmetry Teacher

The Symmetry Teacher

a novel by Andrei Bitov. Translated by Polly Gannon. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014.

Andrei Bitov is a radically independent writer. Even though he is frequently cited as one of the first postmodernist writers in Russian literature, that description does little to define him. It is unlikely, however, that Bitov cares exactly what he is called. What he cares about is language; his long journey as a writer has been centered around exploration of language–its boundaries, semantic twists, and the relationship between so-called real life and literature.

Among his most famous works translated into different languages, are novels such as Pushkin House, A Captive of the Caucasus, and The Monkey Link. The Symmetry Teacher is a three-part “novel-echo,” consisting of seven stories. Bitov states in a preface that he did not write the novel but only made a translation of an unknown English text by A. Tired-Boffin. The novel depicts a life, from beginning to end, of a man called Urbino Vanoski.

None of this is true, or untrue in the practical sense. “Urbino Vanovski” may be an anagram for Sirin\Nabokov as Sirin was Nabokov’s pen name and “A. Tired-Boffin” is most likely an anagram for “Andrei Bitov” where ‘v’ is replaced with double ‘f.’ But, don’t worry, obfuscation is not the author’s intent. The Symmetry Teacher is provocative, frustrating, fragmented, and sometimes annoying. It’s art for the sake of art. It’s not easy to follow and requires a certain patience and some experience as a reader, but broadens enormously perceptions of conventional storytelling.

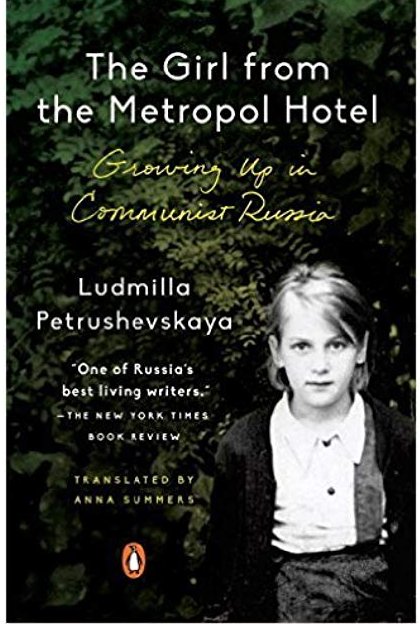

The Girl from the Metropol Hotel

The Girl from the Metropol Hotel

Growing Up in Communist Russia by Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, translated by Anna

Summers. Penguin Group (USA), 2017.

The voice of Ludmilla Petrushevskaya is genuinely unique, no matter what she writes about – the unhappy women of post-Soviet era, tales for kids about Peter the Piglet or, as in this case, stories about her childhood.

Now 80, Petrushevskaya reflects vividly on her life – first on growing up as an orphan, beggar, and street performer, then on the Second World War, her family history, and on her first attempts to write, and finally on her adult life as a prose writer, a playwright and performer.

The Girl from The Metropol Hotel is not a memoir in the classic sense of the word: but a collection of short and very short essays, written disparately and, at some point, collected in a single volume. The narration is as chaotic as the memory itself, but, perhaps, that helps the author from becoming overly sentimental, accusative, or playing to her readers’ sympathies.

Petrushevskaya is elegant and brimming with humor. She is capable of keeping her distance and writing emotionally at the same time. She plays with narration, sometimes allowing it to remain simple in its wording. Although her childhood was miserable, she never goes too far in pointing the finger at those who might be responsible for her and her family’s troubles. The result is a book that makes you, the reader, happier.

Losing Venice (Issue # 3)

a novel by Scott Stavrou

ROGUE DOG PRESS, 2018.

Reviewed by Timea Klincsek

Losing Venice, the engaging new novel by Greek-American writer Scott Stavrou, evocatively describes the life of an itinerant professional who questions, self-reflects, and, finally, reinvents himself in his quest for a sense of belonging. Stavrou has written fiction and non-fiction for numerous publications in the United States and Europe. His short piece “Across the Suburbs and Into the Express Lane” recieved the PEN America International Hemingway Writing Award in 2000. He is also the authored such notable works as the travel book Wasted Away, as well as three original screenplays, including Picketing with Prometheus.

In Losing Venice, Stavrou takes the reader for an intimate stroll across some of the key European cities he lived or worked in: starting in romantic Venetian piazzas and canals, through the medieval, cobblestoned streets of Prague, stopping in proud, divided Budapest, and arriving, finally, at the stunning, rocky, Greek island of Hydra. He describes each city and town with an intensity and vividness that makes them come alive, pulling the reader into the story alongside the protagonist on his extraordinary journey.

Set in the early 21st century, during the Bush presidency, and just after the September 11th attacks, the novel tells the story of Mark Vandermar, a single man in his thirties, haunted by poor decisions in his love life back in San Francisco, and has since been transferred in order to continue his career as a travel marketing professional in Venice. While his Venetian boss is clearly pleased with his performance, Mark feels lonely and detached, isolated from the outside world. As he searches for meaning, he forges an enduring friendship with a local, and falls in love with a chestnut-haired artist whose name he does not know. After her disappearance, Mark falls back into his old-routine of the “Campari Clock”, which consists mostly of day-drinking and daydreaming. Mark’s malaise is soon interrupted by a business-trip to Prague, where he becomes involved in a series of compllex affairs with long-reaching implications.

Losing Venice is a clever, witty, and touching. Its characters vivid and relatable, sprinkled with humor and self-irony, it unfolds in first person as told by its protagonist.

Its a recommended read, especially for those trained expats who have experienced the sensation of being lost, only to be found again. The novel conveys to readers a message about the importance of appreciating the small things: a reminder to find magic in everyday life. It also provides ‘guidance’ on how to make sense of an increasingly complex world, and exhorts readers to resist the temptation to become disenchanted, even, jaded. Most of all, Losing Venice is possessed of a strong narrative voice written in rich, picturesque language.

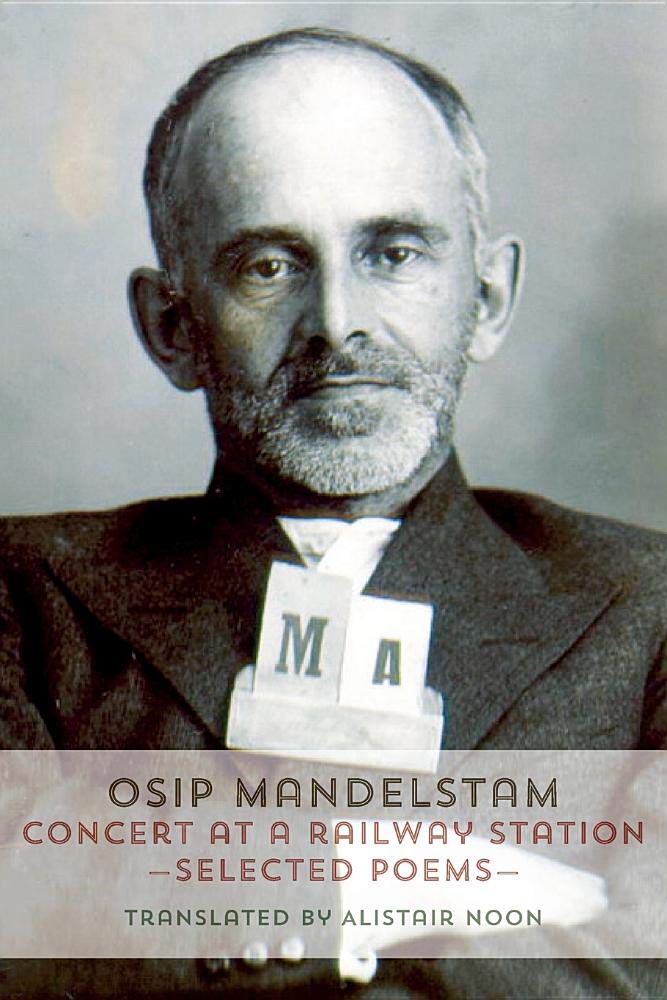

Osip Mandelstam. Concert at a Railway Station. (Issue # 3)

Selected Poems. Translated from Russian by Alistair Noon. Shearsman Books, 2018.

Reviewed by Masha Kamenetskaya

Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938) is one of the most influential Russian poets of the 20th century. His achievements, both personal and

Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938) is one of the most influential Russian poets of the 20th century. His achievements, both personal and

artistic, demand an in-depth explanation, and have outlived him considerably (he was killed in a Gulag at just 47).

According to his contemporaries, he was a man disinterested in worldly possessions and the comforts of a permanent home. He never accrued either—with his wife Nadezhda, he left flats and changed cities, voluntarily or under considerable strain, and with only the books they could carry. This sounds romantic, yet it was anything but.

Mandelstam’s case was a brutal example of era (the echo of which can still be heard), in which even a poet—a bit too independent and educated for his own good and, thus, an irritation to the state—could be effortlessly imprisoned, destroyed, and vanished from all official literature for years. His case is also an illustration of what happens when a poet, a natural-born free spirit, tries to face

down the forces of evil within his country (note: such confrontations rarely end favorably for the poet). Yet, the life and poetry of Mandelstam, above all, shows us that tyrants die but literature remains.

Selected Poems, translated by Alistair Noon, spans the whole of Mandelstam’s writing career and includes those poems that simultaneously sealed his fate and won him his immortality. The poem “We live, but feel no land at our feet”, or “The Stalin Epigram” as it is also known, is not only a remarkable piece, but represented a turning point in Mandelstam’s life, after which he was arrested for the first time and exiled to the Urals. The poem “ It knows me, this city I’d walk till I cried”, which is dedicated

to Leningrad and continues to be cherished by the people of Leningrad/St. Petersburg, paints an artistically intense and affectionate, if slightly sentimental, portrait of the city in which he lived what may have spent the best years of his life.

The pieces from Voronezh Notebooks, also included in the book, survived the Stalin era mostly because friends and supporters hid and/or memorized his manuscripts. The tyrant died, but the poetry didn’t.

Both the selection of these poems and the collection’s title are of the translator’s careful choosing. The book gives us a detailed view of Mandelstam’s legacy; Noon uses Mandelstam’s original texts and titles, along with censored and edited versions (with additional title variants being placed in square brackets). The translator worked off the 2009 Russian edition of Mandelstam’s collected

works (compiled by A.G. Mets) which is reputed to be the most complete and most accurate.

Times of Turbulence (Issue #4)

by Jennifer Walker

Devilspel

Devilspel

Grigory Kanovich (Noir Press, 2019)

As war edges closer to Lithuania’s borders, life in the Jewish community of sleepy, rural Mishkine goes on as usual. Yakov, a gravedigger at the cemetery and his Gentile mother, Danuta, trudge around the overgrown plots, digging fresh graves while their goat chews the weeds around their house and bleats whenever she needs milking. Elisheva, a beautiful Jewish woman, works the land on Catholic Cheslavas’s farm and daydreams of someday making the pilgrimage to Palestine. Their mundane lives unravel, however, as the war gradually infects everything around them.

Where many novels about the Holocaust regale readers of the horrors of concentration camps, mass murder, and houses chalked with the Star of David, Devilspel is subtle and understated. Cracks appear gradually as inconveniences in daily life, while the threat of Germany and the Soviet Union seep continually into the community, a kind of background noise that grows louder and louder over the course of the novel.

Devilspel’s power lies in its subtlety and its humanity. Events take place within the radius of a few miles, wherein each Jewish person is extinguished one by one and the drama of massacre fades to a numbing silence. The novel draws its strength from its strong characters, all of whom are given their own chapter with which to narrate events as they transpire. The story burns slowly, a raft on a stream headed toward a cascade, but Kanovich carries the reader along in its flow, submerging his audience in a world now gone.

Turbulence

David Szalay (Vintage Books, 2019)

David Szalay (Vintage Books, 2019)

On a flight from London Gatwick to Madrid, an elderly, diabetic British woman passes out midway, after returning from visiting

her dying son in London. The narrative is tight, you invest in the characters, but it’s the last we hear from them... at least until the final chapter. The novella charts a bumpy trajectory around the world, over the course of 12 flights, continuing on from Madrid to Dakar, before hopping the Atlantic to Brazil, to Canada, and the US, before turning to Asia then back to Europe, and, finally, ending in London where it began. In each story, characters interact only in passing, often as passengers or servants to another chapter’s protagonist. It’s a journey that circumnavigates the globe from the perspective of each character, providing snapshots of lives we only glimpse.

As might be expected from the book’s title, turbulence is the unifying theme that connects each vignette. Whether this takes the form of literal bumps in the sky as the plane cruises over the Bay of Biscay, cracks forming in a marriage, life-altering events that happen in a split second, or a percolating family conflict where arguments are spoken only as silences.

Despite the brevity of these stories, Szalay succeeds in getting his readers to empathize with his characters, even when they appear for only 10-15 pages at a time. The ripple effect of each event expands outward from the first flight to its final moments in London, when the story comes full circle and a daughter flies from Budapest to London Gatwick to visit her dying father.