Interviews

“Home is a place you want to escape from, but cannot”

Piercing the Limits of Reality: An Interview with Jaroslavas Melnikas

"I am surprised where the story is taking me”

“Home is a place you want to escape from, but cannot”

Masha Kamenetskaya interviews Zurab Karumidze

Writing in a language that is not your native one can be both challenging and rewarding. On the one hand, a writer may feel tied up with vocabulary and grammar constructions that don't naturally belong to him. On the other hand, if a writer succeeds – he gets, at the very least, an access to a broader market and to an additional set of tools for craft and storytelling.

The novel “Dagny, or A Love Feast” by Georgian writer Zurab Karumidze is not only a beautiful imaginative text, rich in its complex world inhabited with characters, both real and mythological, fictional and non-fictional, passionate and desperate, those who were searching for love and, meanwhile, creating art. “Dagny” also shows an example of a successful novel in English, written by a non-native speaker. Long-listed for the International Dublin Literary Award in 2013, published again in 2014 in the United States, just recently the novel has been selected among top 10 books published in Germany, unveiled in third place out of ten.

“Panel” editor Masha Kamenetskaya was curious about what was the reason, or the inspiration push, for Zurab Karumidze when he decided to write a novel in English.

– I know that you've got a degree in English Language and Literature, then PhD for researching poetry of John Donne. And you've translated several of your short stories in English. But writing the whole novel must have been a totally different experience. How did the idea to write a novel in English emerge in the first place?

– The reason was to get broader readership. The Georgian language is spoken by 3-4 million people, out of which 3-4 percent read books. The intention was to “translate” Georgia (in the broadest sense), to make it readable for the English speaking world, which is by far bigger. There were no deliberations, pre-meditations on my part a propos of language; I just sat down to my desk and started writing in English. My wife, seeing that, told me “Are you going mad?” and I said “sort of…”

– For many people who write in a language that is not their native tongue, the whole writing process becomes much more challenging. For me, for example, maybe the most difficult thing is to "switch" the brain to the "English language mode". How was it with you? Did you find it was particularly difficult, surprising, or inspiring?

– The English is my third language (the second being Russian), and for sure I would have faced lots of lexico-grammatical challenges: pre-post-positions, articles (which come with the mother’s milk), some idioms, etc. However, I’ve been fascinated with this language since my childhood – the literature written in it, the songs sung in it by the rock-musicians of 1960s and 70s, etc. The fascination has been so strong, that I attempted writing a couple of short stories and magazine articles. But a novel in one’s third language – that’s pushing an envelope…

Paradoxically, however, notwithstanding the linguistic difficulties and challenges, I felt more freedom while writing in English, than I would have felt while writing in my native Georgian. More freedom in terms of narrative, imagery, associations, allusions, overt or covert references. Imagine yourself standing in front of a forbidden territory, a Zone, and suddenly a voice tells you to get inside and do whatever you want. And I did get inside, and touched, tasted, ate, drank nearly everything I could. I had less restrictions from the inner censorship, I was less self-critical; it’s like going abroad for fun, leaving your homegrown commitments and obligations behind. That's why “Dagny” is like an “intertextual salad bowl” – carrying such a variety of themes, stories, references.

-- "Dagny, or a Love Feast" was longlisted for the International Dublin Literary Award and gained critical acclaim. Were you personally satisfied with a result? Do you have any plans to continue writing fiction in English?

– Being long-listed with such celebrities as Umberto Eco, Haruki Murakami, Michel Houellebecq, Stephen King, David Lodge, was exciting, however awkward. But long-lists are no big deal. I was much happier to find my novel listed 3rd in Germany, among the top-ten books of the month in February 2018. This list is made monthly, for more than 40 years, by 25 leading critics and journalists from Germany (mostly), Austria and Switzerland. That humbled me indeed.

– Have your short story collections and novels, written in Georgian, been translated to English or other languages?

– Only the two of my short stories, translated by myself into English (and edited by an American friend of mine), have been published in the USA (Clockwatch Review, Bloomington, IL), back in 1996. “Dagny” is available in Turkish and German, and not in Georgian.

– When the Georgian publishing house “Siesta” published ''Dagny", did you (or publishers) expect to get an audience from the locals - English-speaking Georgians, or was the target an international audience?

– Both. But the broad English-speaking audience was eventually reached later, in 2014, when the novel was published by the Dalkey Archive press, which is based in the US, but also covering UK and Ireland.

– The characters featured in "Dagny" were based on real figures who may be known to the audience, but not so mainstream as to be known to everyone? It requires a curious mind and some general knowledge from the reader, in my opinion. Do you ever picture your "target reader" while writing, especially while writing fiction?

– As a matter of fact, I was more concerned with those readers who knew the real figures featured in the novel. To an extent I expanded these figures beyond their known shape, but not too much; I stayed with the Aristotelian definition of Mimesis – depiction of something that happened, or could have happened. Some Georgians may criticize me for “going too far” with Vazha Pshavela – an amazing Georgian poet: a highlander man, who proved to be the first Modernist in our literature… But look at Ken Russel’s movies, how he pictures Liszt, Wagner, Mahler, etc.

A propos of the “target reader” – while writing, I usually have 12 or so people on my mind, whom I know, and whose tastes I “observe”, and this is my virtual audience.

– Are there other Georgian writers who also make the effort to write in English? Or are there any writers from overseas living in Georgia? And, how diverse are literary circles are in Georgia?

– Literary scene in Georgia got rather vibrant, as this year Georgia is going to be the Guest of Honor at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Georgia’s National Book Center has attracted many publishers from Europe (especially Germany) to translate and publish contemporary and classical authors and present them in Frankfurt.

I don’t know any other Georgian writer who would have made an effort of writing in English – at least a published one. There are several Georgians writing in German – like a young lady Nino Haratishvili, who is based in Germany and her novels won acclaim in this country; or Givi Margvelashvili – an old timer in German literature. A couple of overseas writers show up from time to time in Georgia and write about the country – a young American author Tara Isabella Burton is one of such. Wendell Stevenson, and American author woman, was based in Tbilisi in late 1990s – early 2000s, and she wrote a book on Georgia – “The Stories I Stole”.

I don’t know any other Georgian writer who would have made an effort of writing in English – at least a published one. There are several Georgians writing in German – like a young lady Nino Haratishvili, who is based in Germany and her novels won acclaim in this country; or Givi Margvelashvili – an old timer in German literature. A couple of overseas writers show up from time to time in Georgia and write about the country – a young American author Tara Isabella Burton is one of such. Wendell Stevenson, and American author woman, was based in Tbilisi in late 1990s – early 2000s, and she wrote a book on Georgia – “The Stories I Stole”.

– Are the contemporary bohemian circles of Georgia, somehow, worth being portrayed in fiction?

– Contemporary bohemians differ from their “ancestors” living in 19th century and fin de siècle. Contemporary Georgian bohemians are clubbers, they don’t drink but they smoke weed, are politically active leftist-anarchists, some of them got jobs in local NGOs, some trying to find their place in arts or writing or music or cinema, some are gay, some straight, but defending the gay rights, etc. Are they worth being portrayed in fiction? Yes, of course!

– When it comes to immigrant/expat writers, these people usually travel a lot, explore a lot, but cannot usually find an answer to the question of where their home is. And the theme for our first issue is “home”. I know this question may seem a bit tacky but still: how do you, Zurab, define “home”?

– Writers are homeless, on the other hand – wherever they put their hat is their home. Take Hemingway – a guy from Illinois, who found his homes in a Parisian café, Spanish Corrida, Civil War battlefield, or Cuba. James Joyce epitomizes such homelessness through his life and the paradigm of Ulysses in his major novel.

I would define “Home” in a sort of antinomy way: Home is a place you want to return to, but cannot / Home is a place you want to escape from, but cannot.

Piercing the Limits of Reality: An Interview with Jaroslavas Melnikas

Panel editor Jennifer Walker interviewed Jaroslavas Melnikas on penning prose in multiple languages, whether place influences his writing, and discussed his collection of stories and the inspiration behind them.

- "The Last Day" is the first of your books to have been translated into English. You’re both Lithuanian and Ukrainian, and you’ve lived and published in France, do you write in all three languages or do you prefer to write in one language? If you write in different languages, do you feel there is a different style or persona that comes through, say is there anything different between writing in Ukrainian, Lithuanian, and French?

- Besides the three languages you mentioned, I also write in Russian. Language, for me, is a tool, it’s the material I work with: many painters have also been sculptors, they have used different materials. Painters use watercolours, oil paints, ink, pencil. To write in a foreign language is to set a challenge for oneself.

In every language I remain the same, that is, myself. And my style remains pretty much the same. Perhaps the ease with which I switch from one language to another is since my language is deliberately minimalist. I don’t play with words; I don’t use lots of epithets, or dialect. What is important in my writing is the psychology, the archetypes, the characters, their internal logic and the deeply hidden idea. On more than one occasion critics have noted that my prose is straight-forward to translate in another language. Perhaps because of that, I find it easy to write in various languages or translate my writing from one language to another.

- I thought the stories in "The Last Day" were fantastic, and I particularly loved how you took average, everyday people and placed them in extraordinary, magical realist situations, like finding out the date of their death and how one would handle knowing the fate of their loved ones to the case in The Grand Piano Room, where protagonist’s favourite rooms in the house just start vanishing, and other extraordinary situations like the art house with the endless film in the appropriately titled It Never Ends. Was this a concept you came up with for your short stories or was it more natural than that?

- What I write doesn’t spring from the concept. If it did, the writing would be dead; it would just be the illustration of an idea: This is not how it works. The fact is that in every situation, however concrete, that humans are involved in, I see the commonality, archetypes. Every moment in a person’s life is powered by its particular logic. I trace that logic to its extreme. Often it will pierce the limits of reality, as in the short story, "The Last Day" (which in Lithuanian and Ukrainian was called The Book of Fates). Or as in my novel, Masha or Post-Fascism, which took the ideas of the Nazis to their logical conclusion, imagining a Third Reich which existed for a thousand years. One of my Ukrainian readers noted that I must have been good at mathematics when I was at school because I have a very logical mind. The fact that he

had sensed that amazed me. It’s true that I was the best mathematician in my school; I left school with the gold medal for mathematics. That particular reader, as it happens, was a Doctor of Physics, the head of the Department of Theoretical Physics at the Ukrainian Academy of Science.

The whole interview is published in Issue # 2 (click download), November 2018.

"I am surprised where the story is taking me"

It’s hard to name an artistic field in which Istvan Orosz is not hard at work. He is a visual artist, a printmaker, an animator and film director, a graphic designer and, since relatively recently, a writer. He has become famous in Hungary and abroad. His solo exhibitions take place all over the world—from Turkey to Russia. He is the winner of numerous awards, although he insists that accolades are unimportant.

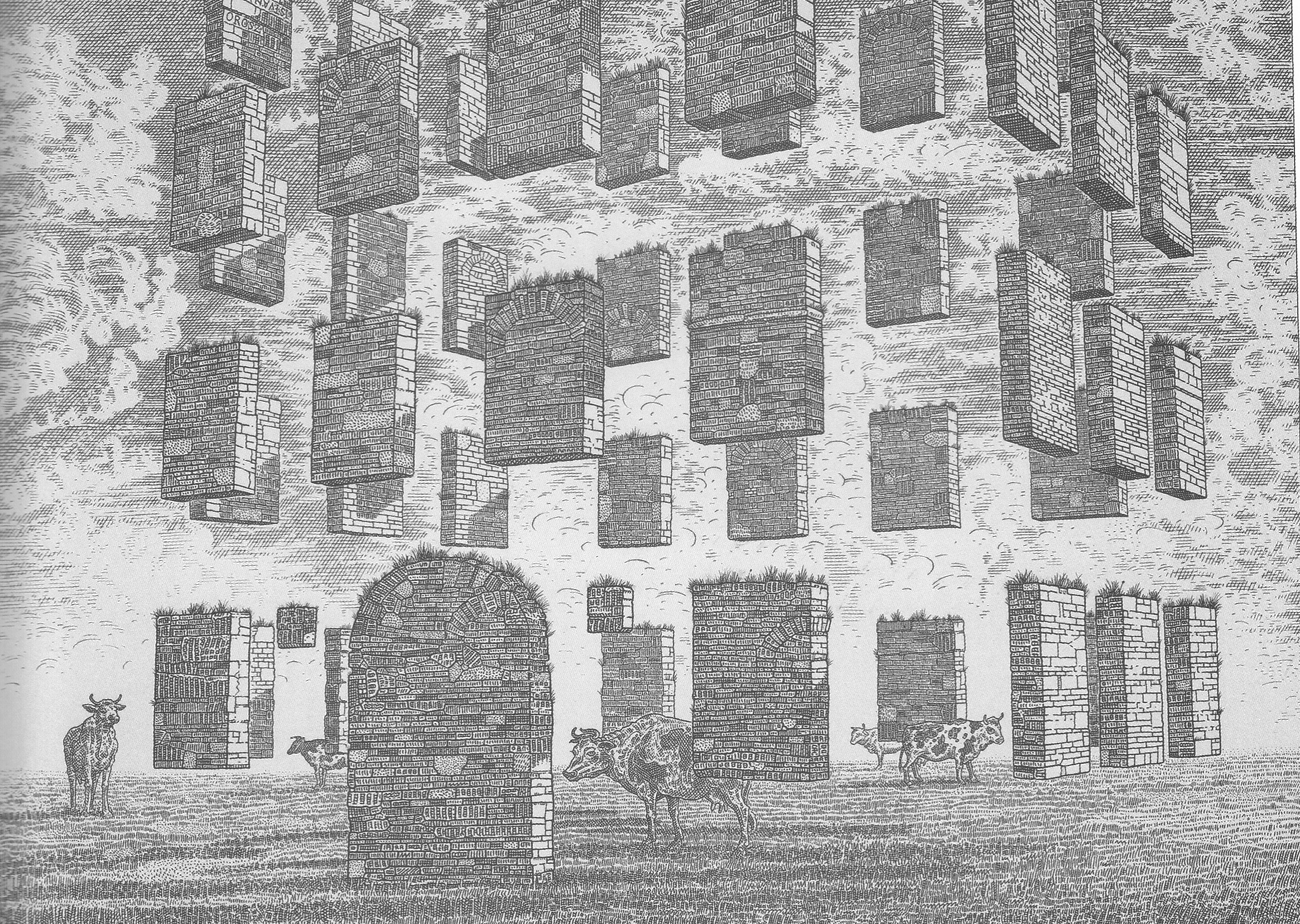

Absence IV by Istvan Orosz

Orosz published his debut novel “The Ambassador and the Pharaoh” (“A követ és a fáraó”) in 2011, and his most recent novel “Sakkparti a szigeten” (“Chess on the Island”) in 2015. Since then “Chess on the Island” has been translated into Russian, and is now being translated into Slovakian and Italian.

Orosz published his debut novel “The Ambassador and the Pharaoh” (“A követ és a fáraó”) in 2011, and his most recent novel “Sakkparti a szigeten” (“Chess on the Island”) in 2015. Since then “Chess on the Island” has been translated into Russian, and is now being translated into Slovakian and Italian.

This issue of Panel includes an exclusive English translation of a chapter of that book and, seizing a rare opportunity, Masha Kamenetskaya met with Istvan Orosz—and asked him how an artist became a writer.

-- The subject that you've chosen for your book is very specific. The core of the story is a chess match, played by Vladimir Lenin and — a bit less famous figure—Alexander Bogdanov, while they were on the island of Capri, visiting another important person of the time—the Soviet writer Maxim Gorky. Why did you choose this as the subject of your novel?

-- It all started with a photograph. As a visual artist, I am interested in finding rare or unusual, or otherwise interesting images. I am very much into optical illusions, too. And once, more or less accidentally, I came across a photograph of the chess match between Lenin and Bogdanov. But it was not just a picture. It was itself an optical illusion. You see, during the Soviet several versions of the same picture existed: the number of the people depicted in the photograph was different. Usually, those who became unwelcome in their own countries, were just erased, wiped off. For instance, there are versions of the photograph with just five people, instead of nine. This illusion inspired me.

Plus, I like playing chess. Soon after I found the photo, I also found the scheme of the chess tournament and made an animated film, a move-by-move reconstruction of that competition. And it was only after all that I started working on a book.

-- It seems like you managed to tap into such a rich vein of material in your book. How did you manage to dig all this stuff up?

-- Well, one thing led to another. At first, I read works of Lenin, and of Gorky, translated into Hungarian. I continued my research, digging through documents in English and even a bit in Russian. I was lucky to meet a translator, Vyatcheslav Sereda. he helped me a lot with the research, and even corrected some inaccuracies when, later on, he was translating my book into Russian. So, it it was just one of those things that happened over time.

-- To be honest, I was unsure of how to treat your book—it seems so documentary, but something about it, the narrator, for instance, gives the reader a sense of its fictional nature.

-- I would say it is semi-documentary and semi-fiction. It is definitely more than a collection of facts, more than pure documentary research. I worked with real people and with credible facts, but the way I worked with them, lets say that I wrote a kind of “documentary legend”, if . I observed and researched the details and stories behind the facts in a primarily “fictionalized” way. When I begin to make my own interpretations, the result is fiction.