Non-fiction

The Magic of Cars

A City with Two Faces

The Magic of Cars

Essay by Duncan Robertson

I have tried, before, to write about the magic of cars.

If you have just boarded an airplane with all your possessions and regurgitated them into a breadbox apartment in an urban center on the other side of the world, one thing that you are unlikely to have packed is your car. Depending on the caliber of public transportation, you may also be unlikely to ride in a private vehicle for some time.

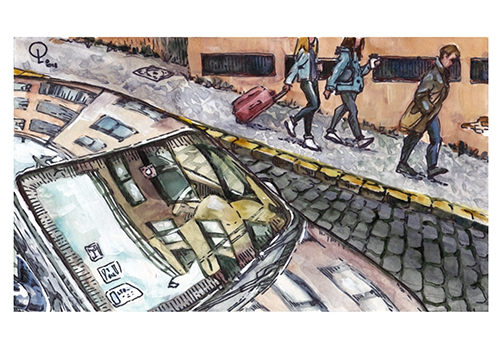

The whole experience of the car changes in its absence, and upon reentry into the car environment a city changes too. It's alleys unkink and its streets unravel. The articulate speed of the car reveals and makes available the outer strata: population centers of second and third tier significance, forests and mountains, lakes and beaches and difficult to reach attractions set outside the city center, all of which would normally require the close reading of an arcane train schedule. After some time apart from the car, you may find yourself marveling at its upholstery and power windows.

It travels at middle speed, between a pedestrian crawl and cruising altitude. Its closest relatives are the train or the bicycle, yet neither are very much like the car. It demands the trappings of a middle life. You need a substantial income for the payment of insurance, for gas and regular maintenance. You must collect the relevant paperwork from government offices, in order to take a driver's test in a foreign language. You must apply your signature to many forms you cannot understand.

I am discussing the car, or the change in the experience of the car, because it follows a pattern familiar to any long-term traveler. First, it disappears under diverse new methods of conveyance (metro systems, tuk-tuks, shuddering trams), then, gradually, it is glimpsed through taxi rides or in afternoons spent borrowing a friend's van to move apartments. Finally, it is resurrected via airport shuttle, so, the last time you navigate the streets of a foreign city where you have lived for months or years, they shoot by at pace, filmic, replaced by terrain along the highway. Often, this final leg is accompanied by music in headphones, setting the tone for a departure fugue which lasts all the way to cruising altitude, only dispelled once it comes time to decide whether to purchase an expensive sandwich of mediocre quality or to wait and grab something in Frankfurt.

The car, inseparable from life in many parts of the world, is first discarded, then grows exotic, finally revealing itself through an altered lens. The experience of the car, like the experience of living abroad, ends in a return, although it is seldom the return we expect. This is because, in a new country, one is as foreign to the car as one is a foreigner in the larger sense. Cars follow the pattern of foreignness - of everything about home which is taken for granted, lost, and rediscovered.

The absence of friends and family is less often experienced in stabs of homesickness, and more commonly experienced for what it is, an absence. During a holiday it might be felt so acutely as to become explicit, but usually presents as a background hum, a whine, which at the outset of any serious intercontinental relocation is undetectable; to be somewhere else was the point, after all. Then, slowly, as you pass families on the sidewalk or watch children leaving school, all those things which are 'homey' accumulate a distant, glossy quality. The hum pitches up slightly, detectable in a moment of dissonance. Weren't you once a child in a school nothing like this one? Wasn't there a time when it was possible to communicate with shopkeepers? In one place there are rules that govern the volume of conversation on the subway. In another place, you must never call an occupied seat 'not free,' only 'taken'. In a third place, a young person offering to split a restaurant bill with an older person is a matter of grave concern, signaling a strain of impudence so repugnant as to call into question the purpose of having enjoyed a meal together in the first place. These rules are not fleshed out systematically, but piecemeal, sometimes second hand, against one’s own preconceived notions of what is normal and with the help of people working against their own language barriers. There are misunderstandings and false starts. There are flabbergasting indiscretions, self-consciousness of an order that approaches radioactivity. If you are ethnically or culturally aberrant, there is the feeling of being watched.

Then, one day, an inscrutable shopkeeper collars you as you are walking by his place of business. People are packed into his corner store at the end of a street where he peddles candy cigarettes and newspapers and espresso from a coffee machine. They are passing around pictures of a baby, not a phone with baby pictures on it, but glossy prints. While you have been hunched over your soup, people have died and been born and fallen in love and overeaten at lunch and nodded off at work in call centers. You nurse the champagne in your white plastic coffee cup and unselfconsciously adore the picture of this newborn baby, the picture of a stranger's baby, as it circles the group in the corner store. You are receiving the pictures, and they are no longer baby pictures; they are baby pictures again and for the first time. Have you become sentimental? The opposite. You have been cordoned off. This is the first crack in the veneer of strangeness, through which you now spy regular life, thrumming along unperturbed by the imagined slights and dangers of an alien country - totally mundane in its own reckoning - and it comes as a tremendous relief. How silly you have been, how paranoid and sensitive. No two places yet exist that in only one, children are born.

You will never count change closely again, in this store. You will never be as embarrassed about how poorly you speak the language, in this store. You will be more patient and more polite and more awake.

But, like learning a language long enough to realize that people everywhere are talking about the same things, the significance of this will fade. The feeling of seeing clearly will tarnish.

You may even realize, one day, that you are bored, unable to recall what was important about handling baby pictures or riding in a car. You will return home, unsure of what drove you abroad in the first place, or, if you are still possessed of the energy and presence of mind, you will move and begin the process again: each iteration more or less transformative, more or less isolated, more or less revelatory.

So what have you learned? That there is divinity in these mundane things, these car rides and first verb conjugations and glossy prints? Not more so than there is mundanity in the divine. Perhaps, only to treat the old adages with a grain of salt. Home is not always where your heart is, sometimes it is nowhere at all. Maybe you can't go home again, but you might discover it one afternoon while out for a walk.

Or that, for those that keep an even keel, persevere and give others the benefit of the doubt, there exists the possibility of an organizing experience, an impermanent powerful crystallizing story of return, which, in its upholstery and power windows, its great modal velocity, does not follow the linear geometry of departure and arrival, but etches a circle onto the surface of a sphere.

Published in Issue #1, May 2018

A City with Two Faces

An essay by Masha Kamenetskaya

Liberty Bridge over the Danube in Budapest attracts many eccentrics in summer. They climb up the bridge, or stare at the water, or sing, or drink – they can be met there at any time of the day. Just recently, when passing the bridge, I saw a couple – a blue-haired girl and a bald man, both bare-foot, very slim, the girl holding a camera and the man an unlabeled bottle. I heard the blue-haired girl say to her companion, “This city is like Gemini in the zodiac. You've got two personalities and never know which one you’re dealing with.”

It was one of the best descriptions of Budapest I've ever heard. Budapest is indeed a city with

two personalities.

Budapest is the beautiful capital of a country that is only vaguely known to those not living in Europe. I watched, for instance, an episode of the television show Homeland that was shot in Budapest but was set in Moscow. In a hurry, the filmmakers failed to replace street signs and the extras spoke Hungarian. Very few audience members (according to television ratings and Facebook discussion threads) recognized either Budapest or the language.

Also, Budapest is amazingly diverse, truly multicultural. During a stand-up open mic at some underground venue one may find, in the audience, the entire globe encompassed by a tiny room – literally from New Zealand to Norway. Budapest attracts people from all of the world to stay for short or long periods and, somehow, wins their hearts.

Budapest is relatively cheap and it's dripping with culture – almost every night there is something to do – big concerts and local underground events.

On the one hand, most budapesti speak only Hungarian. On the other hand, Budapest has became a friendly home base for many English-language projects including ours – Panel.

Budapest is cozy, not too big and not too comfortable, and it never feels like home – that is, if one considers home to be a thoroughly-explored place with no surprises left to find.

The whole essay is published in Issue # 2, November 2018