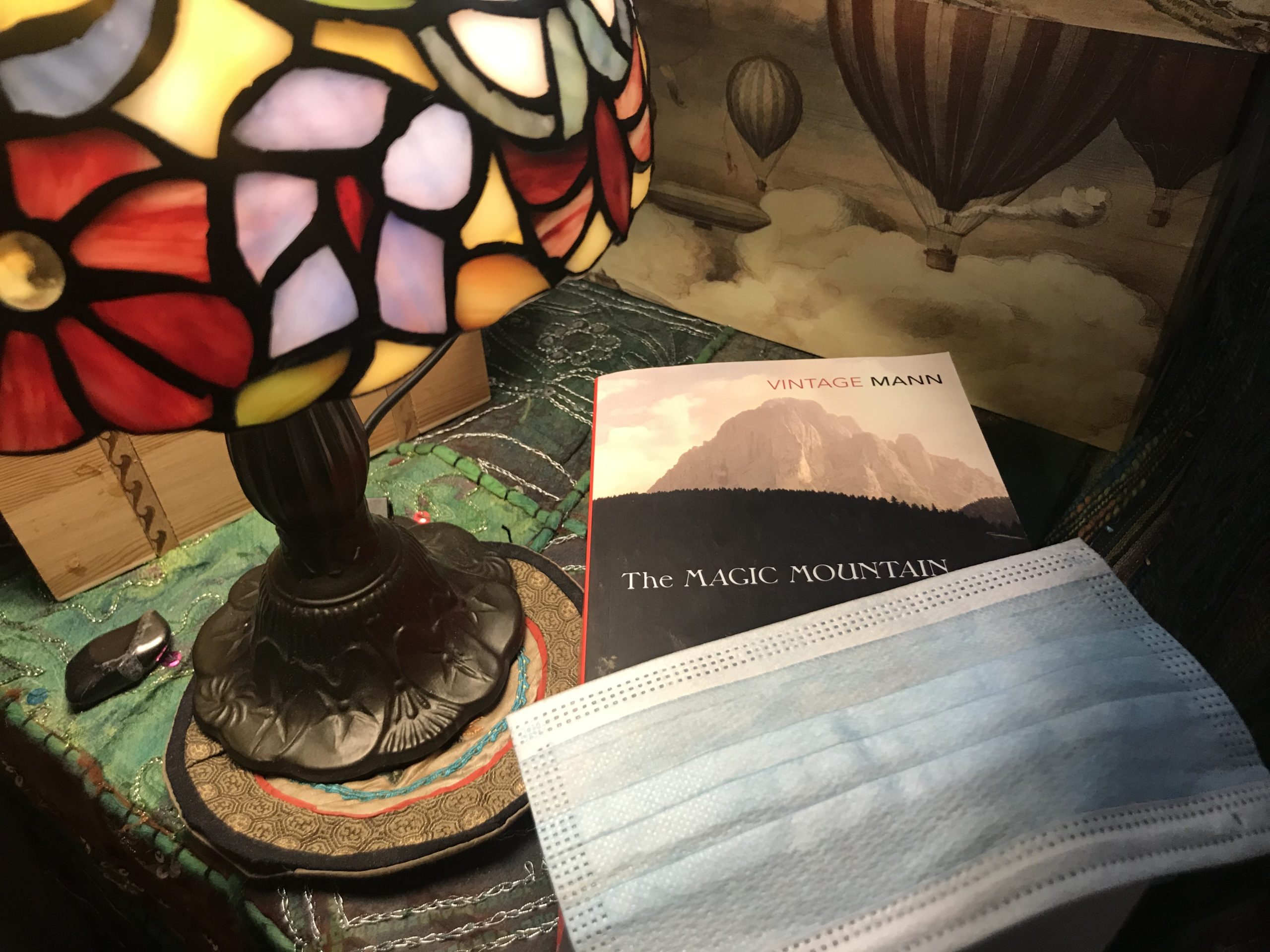

Reading Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain in the Time of Covid

As I reached the top of Gellért Hill, Hans Castorp got out of the carriage at the Berghof Sanatorium in the first chapter of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. With Budapest in lockdown, my only contact with the outside world was my daily hikes up Gellért with an audiobook to keep me company the way Hans Castorp did as he accompanied his consumptive cousin Joachim Ziemssen on his daily constitutional up into the Swiss Alps. Audiobooks and walks replaced the surrealist parties, literary readings, and late nights in dingy bars, as my body clock shifted to a time when morning dew sat on the spring blossoms, and it was easier to avoid people actively. I soon began to measure time by the changing vegetation and the books I consumed. March became a month decorated with almond blossoms and the bawdy tales of the Decameron; April turned into a binge of Nabokov’s most significant works (that were not Lolita) perfumed by the scent of blooming lilacs and acacias; roses and wildflowers flowered in May as I fell into the intense friendship of Narcissus and Goldmund in Hermann Hesse’s best book. June carried me up to The Magic Mountain just as the lavender began to flower.

This isn’t the first time I’ve visited the world of The Magic Mountain. I delved into Thomas Mann’s magnum opus I was alone in Venice nine years ago just days after submitting my PhD thesis. I thumbed through the pages with an Aperol Spritz in hand as gondolas sailed past on cliched canals. I was exhausted from researching the nuclear structure of tin isotopes, and even though I had this strange curiosity in the sciences the way Hans Castorp did, I am ashamed to admit until recently I forgot the core plot of the book. At the time, I had been immersed in its prose, but some books leave you with a kind of narrative amnesia. Sometimes you remember an impression, the atmosphere, a memorable character or a single scene, but your brain erases the book’s memory after a time to make room for more information. Much like the content of my PhD thesis nine-years later in a life of post-physics recovery, I forgot much of The Magic Mountain.

After almost a decade, I felt a pull back to the Berghof, much like many of the consumptive patients who eventually returned over the course of the novel. Once you’ve been to the Berghof, chances are you’ll come back. So, I decided a pandemic was a good a time as any to return to The Magic Mountain.

I believe that many books are meant to be read twice, as we gain something new from them once we’ve lived more of life. In my 20s, the slow pace of Hans Castorp’s life in the Alpine sanatorium peppered with philosophical discussions and existential musings of time didn’t resonate with my fast-paced life in bohemian Madrid when I was a scientist by day and an aspiring writer by night. However, in my 30s, when life has forced me to slow down while stuck in a pandemic in Central Europe, I can relate.

The novel rolled along audibly with me on my morning strolls. The views at the top of the hill treated me to the city fanned out below in miniature as the Danube snaked its course from north to south, splitting at the tip of Csepel island before making its own way, only to reunite out of my sight. The light changed each day, painting the water blue some mornings, others grey and swelling, and only once as a mirror that reflected the bridges in inverted copies. I trod the same paths, measuring the transition of time by the changing vegetation while listening to the narrator dramatize Hans and Joachim’s discussions about the nature of time passing.

Hans arrived at the Berghof for three weeks—a respectably long time for someone who came from the real world known as the “ Flatlands” or “Down Below”—but for the denizens of this alpine sanatorium, the smallest denomination of time is a month at least.

“Three weeks are nothing at all, not to us up here—they look like a lot of time to you, because you are only up here on a visit, and three weeks is all you have,” Joachim said to Hans upon his arrival on his three-week holiday to visit his consumptive cousin, “They make pretty free with a human being’s idea of time, up here. You’ll learn all about it. One’s ideas get changed.”

The passage of time becomes a leitmotif of The Magic Mountain. In the beginning, time cascades over the first three weeks that take up 160 pages of the 720-page books spanning seven-years; time quite literally slows down as the page numbers increase. In January, those of us who lamented the slow passage of winter are shocked to find the months have skipped by and more than half of the dreaded 2020 is over. On first impressions, book’s premise of a seemingly ordinary and healthy man who turns his three-week holiday into a seven-year stay at a sanatorium feels somewhat surreal, but as many of us have noticed it’s easy for time to slip by when we are isolated from the real world.

You see, despite the illusions of health, Hans Castorp has lung problems. It turns out that like his cousin, he also has symptoms of tuberculosis. The cynical engineer who took life easily confronts the shallowness and mediocrity of his existence as the slow pace of sanatorium life transforms him. He delves into intellectual passions as he thumbs doorstepping medical tomes, studies the stars on his nocturnal rest cure on his balcony watching the sky under a fur-lined sleeping bag, and botany on his walks on the paths snaking around the Berghof. He also loses himself in the philosophical rants of the eccentric Lodovico Settembrini, a humanist intellectual, and then later on with Leo Naptha, a Jew-turned-Jesuit living down in the village. Castorp also cultivates a romantic obsession from afar with one of the patients, Clawdia Chauchat, only declaring his feelings for her tragically on the night before she is due to leave the sanatorium, taking an x-ray of her lungs as a keepsake before she departs. As many of us have had to slow down our lives and put it on pause, it’s easy to feel empathy for poor Hans Castorp whose planned out life is shelved while his health still poses a risk to him. We may not be consumptive patients in need of rest cures, but we resonate with his experience; that feeling of losing control of our hopes and dreams when a threat to our health consumes us. The Magic Mountain is not a book for a fast-paced life, which is why it took a pandemic and a lockdown for me to connect with it.

There is another, darker, more existentialist sense of dread that plays out in the book. Just before leaving, Clawdia Chauchat reveals to Hans Castorp there is a rumor his cousin is dying. Yet the cousin declares to the director, Dr. Behrens, that he has had enough of the Berghof will return to the Flatlands to enroll in his regiment. Joachim, like Hans and many other patients, suffers from a prolonged stay with no foreseeable end. The months soon slip into years, and it seems like there will never come a day when the doctors at the Berghof will proclaim their patients well enough to re-enter the real world. Many defy the doctors’ orders.

“I cannot wait any longer. Originally I was to have been three months. Since then it has increased, first another three, then another six, and so on, and still I am not cured,” said Joachim.

This feeling of the months rolling past with no end in sight has become our reality. At the beginning of the pandemic, we thought things would be back to normal by the summer. Midsummer has passed, and although lockdown has relaxed and we’re drinking beers on terraces, uncertainty and a threat of disease still flicker in the air, as the second wave already rears its head in Asia. However, many, like Joachim, don’t care anymore. They don’t want to wait longer for a cure even if there is a chance they could die—most who leave the Berghof return still sick.

The story of The Magic Mountain sits on the cusp of a changing world—just before World War I breaks out. Like 2020, the world of Hans Castorp sits on a knife-edge of uncertainty and the world is about to change. The Magic Mountain may be a slow-moving book that is a throwback to an age of Central European decadence, but there is so much that resonates with us today. Although the shock and lockdown of the pandemic may have eased, at least at the time of writing, I believe many of us can go into this epic Bildungsroman with empathy and understanding many of us didn’t have before the age of Covid-19.

Leave a Reply