Baltic Tales in Translation

Jennifer Walker interviews Jayde Will

The Baltic States of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia come with a rich and diverse literary tradition that we feel is underrepresented in the international literary scene. Ever since our very first issue of Panel, we’ve wanted to highlight writers and poets from the Baltics. Over time, we’ve been lucky to build a relationship with Noir Press, an indie publisher specializing in contemporary Lithuanian books in English, and Baltic-language literary translator Jayde Will.

Jayde Will is a writer and translator from the United States currently living in Riga, Latvia. He has translated novels, poetry, flash fiction, and short stories from many Baltic languages, including minority languages, like Latgalian, which is primarily spoken in the Latgale region in southeastern Latvia. We’ve published his Latvian translations in Panel Magazine on several occasions: an extract from Albert Bels’s novel Insomnia in issue 3, and flash fiction by Rvins Varde and poetry by Alvars Madris in issue 5.

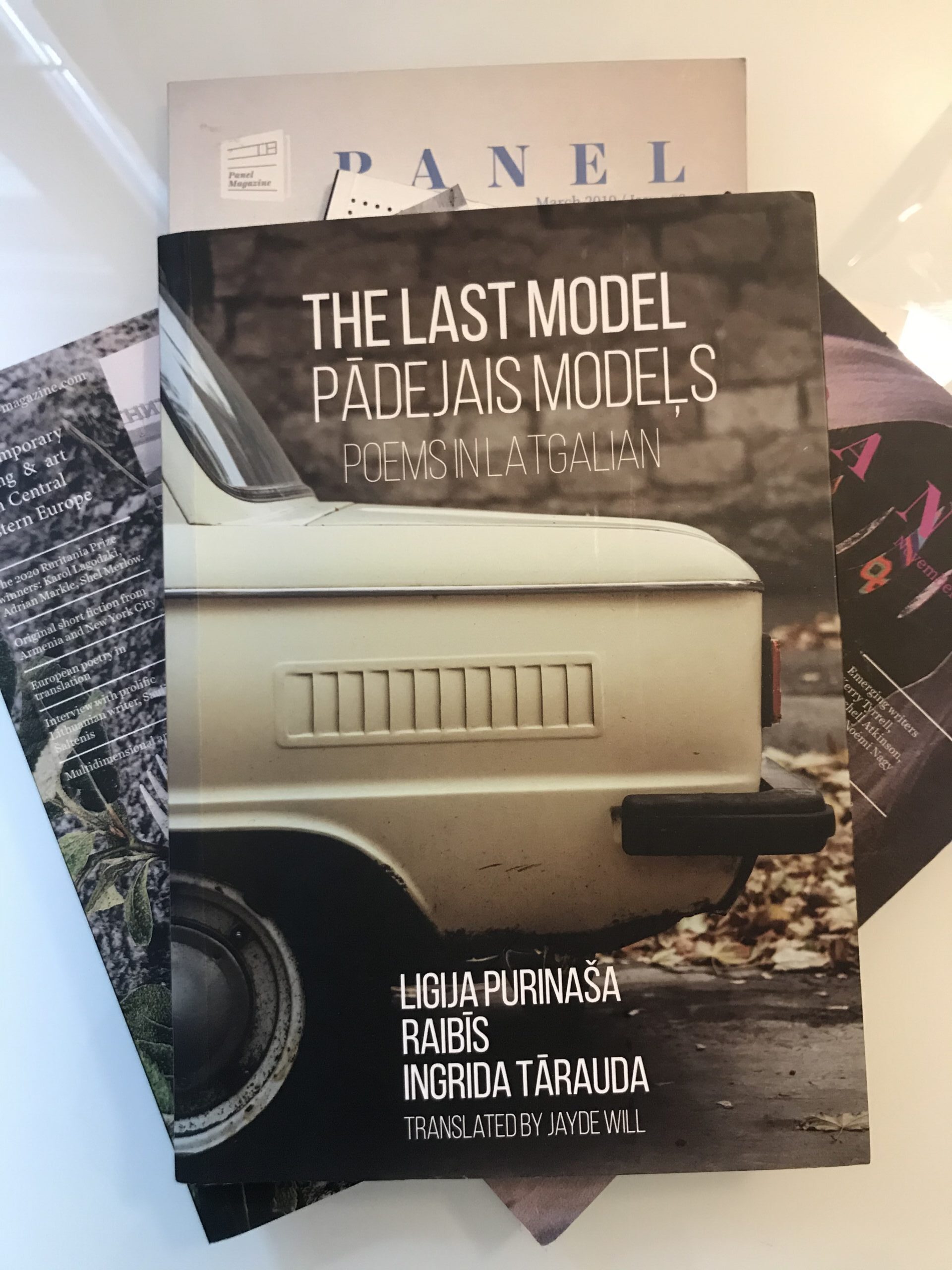

In 2020, Jayde compiled and translated a bilingual anthology of Latgalian poetry, The Last Model, so for our upcoming issue 7 of Panel Magazine, we’re proud to publish exclusive translations of Latgalian poetry by Ligija Purinasa and Latvian poetry by Krista Anna Belsevica.

We wanted to talk to Jayde about his work and life as a translator, the Baltic literary scene, what he recommends we read from the region, and more.

How did you get into translating Baltic Literature as an American? Do you have any family connection to the region, or do you have another story that drew you to the Baltic States?

I was a foreign student in Tartu, and started studying Estonian. I also traveled around a bit, and fell in love with the languages of the region. I started to translate more seriously around 2004, and also got involved with literary translation, at the beginning from Lithuanian and a bit from Estonian, and then from other languages. I don’t have any roots in the Baltic, but my family history is tightly woven with Central Europe in what today is Poland and the Czech Republic.

You’ve translated a wide body of work in many Baltic Languages, including the main languages of Latvian, Estonian, and Lithuanian, as well as minority languages like Latgalian, what has been your favorite work you’ve translated in each language?

With Lithuanian, it has to be Ricardas Gavelis’s novel Memoirs of a Life Cut Short – it was something I had dreamed of doing for about a decade before a publisher was found. I find that the book encapsulates much of the Soviet-era mentality that I found when I came to the Baltics, and which is still around. It illustrates many of the traumas any country that lived under occupation has to deal with, but it is also specific to Lithuania and its mentality. It’s one of the best books on the country in general, and when we think about all kinds of classic authors from Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, Albania, the former Yugoslavia, it provides an overview of the rotten insides of the system.

As for Latvian, it’s hard to say, as I have done both poetry and prose, and I have to say, I love all my translations. If you want to know the one that was perhaps most satisfying, it would be Alberts Bels’s Insomnia, which also received a fair amount of press and also got several positive reviews in the UK and elsewhere. It is also in the same vein as Gavelis’s novel, but Bels’s Insomnia was written in the 1960s and subsequentially banned from publication till the late 1980s. I think both the style, which was an early form of post-modernism, coupled with the fact that he talked about the rotten system, the occupation, and society in general is simply amazing, and all that in just about 160 pages.

As far as Estonian, in recent years I have concentrated on poetry, as I have poets I have worked with quite extensively over the years (Eeva Park, Mats Traat, and Maarja Pärtna), and also others I’d like to. I guess Estonian poetry also fits a lot to how I learned the language – by speaking, by learning everyday life, and I feel that by and large contemporary Estonian poetry is just that – the everyday, the struggle of life, nature, and oneself. Prose takes on a bigger scope, though I have my favorites there as well.

Latgalian is a relatively new thing for me – I started learning it recently due to the poetry of Anita Mileika and Raibis, and then suddenly Latgalian literature and authors started becoming quite popular, so I realized there was a part of literature in Latvia that needed to be promoted in other languages, which resulted in The Last Model, which is an anthology of modern Latgalian poetry from three authors – Ligija Purinaša, Ingrida Tirauda, and Raibis.

How do you find the literary scene varies between Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania? Is there anything you find uniquely Latvian or Estonian, for example, when you read literature from that region?

I came up against the same question when I compiled and edited an anthology of Baltic poetry in 2018. I had to write the introduction, and I quickly understood that even being in the know about general trends simply doesn’t give you the kind of information you need to make an informed introduction. Things can change so quickly, and frankly, it’s tough to come up with good comparisons.

I think the problem is that readers and publishers who are not very familiar with small countries think “oh, there’s just 1.9 million people living in Latvia, it must be easy to get an overview of things” and it’s not. Even to do a general overview in one calendar year can be tough if several good books come out. Add another couple countries to the mix when you are making comparisons, and you got a lot of reading to do?

At the moment in Latvia, historical prose is all the rage, though perhaps it’s important to note that historical prose in this case is not a Victor Hugoesque Les Miserables or War and Peace variety, but more about talking about historical events and figures from the last one hundred years. Also, the short story has come back in fashion, with several primarily female short story writers coming to the fore. In general, female authors are extremely well-represented in the country, with perhaps Latvia’s most internationally known author being Nora Ikstena and her book Soviet Milk, which was widely reviewed in the foreign press, with the rights sold to 19 countries at present.

I think you also have genres that are more popular in one country than another – for a long time the literary essay (creative essay, speculative fiction, however you want to call it) was a big thing in Lithuania, but largely absent in Latvia and Estonia. However, in Estonia there was a Gothic horror stream you didn’t find in Latvia or Lithuania. Crime also became more of a fashion in Estonia than Latvia or Lithuania, but those sorts of trends change over time.

As I have been more focused on reading authors from Latvia, I can’t say I have had a chance to do a lot of reading in Estonian and Lithuanian, but there are good periodicals that help me keep up at least a bit with what is going on there.

Do you have any favorite authors you can recommend for us? If we’re starting out with Baltic Literature, do you have any recommendations for English speaking readers?

Of course, Soviet Milk by Nora Ikstena is a good start, along with Zigmunds Skujins’s Nakedness. With Estonian literature, I’d say Rein Raud’s The Death of a Perfect Sentence is a good start, along with Mati Unt’s Things in the Night. With Lithuanian literature, Alvydas Slepikas’s In the Shadow of Wolves is a great short novel about the Wolfskinder, or “wolf children,” largely German, who escaped from the Soviets in East Prussia during World War II and found refuge with Polish and Lithuanian families, hiding their identity for much of their lives. There were also several poetry collections that came out from Baltic authors like Lithuanian poets Gintaras Grajauskas and Aušra Kaziliunaite, as well as Latvian poet Arvis Viguls, and Estonian poet Doris Kareva. I think the 2018 London Book Fair, where the three Baltic countries were the Market Focus countries, really had an impact on the publishing of Baltic authors in English. It was the first time there was such a plethora of English-language translations. As we know, the English-speaking world has a rather small percentage of English translation making up its market, and it’s even tougher for small countries as a result to make their mark. I think we started well, but the work is not over. You have to think long-term, otherwise you won’t go any farther.

I want to talk a bit about your translation of minority Baltic Languages, most particularly Latgalian. You’ve recently published an anthology of Latgalian poetry “The Last Model” and we’re excited to feature some of the poems you’ve translated by Latgalian poets in our upcoming issue of Panel. Can you tell us a little about the language and its literary scene?

There are approximately around 160,000 speakers of Latgalian, which is primarily spoken in Latgale, the southeastern part of Latvia. I am not sure about active writers, but I am happy that their books seem to be getting more attention from the literary establishment in Latvia. Books by poet Anita Mileika, Raibis, Ilze Sperga, and Ligija Purinaša have been nominated for the Annual Latvian Literature Award in recent years (known as the LALIGABA award in Latvian), and also have won awards at the Bonuks Awards, which is the main Latgalian awards ceremony for achievements in Latgalian culture. The Last Model was also shortlisted for a Bonuks Award, which I was quite proud of, because the competition was rather fierce this year.

How did you get into translating Latgalian poetry?

I started with the poetry of Raibis, whose poetry book launch I went to in Riga, and over about a year, we talked about his collection, and I started to slowly translate some of his poems. Then I began to dive a bit deeper into Latgalian literature, and around the same time several books came out – Ingrida’s book “Feelings,” Ligija’s book “Woman”, and a few others.

What do you find most unique about Latgalian literature?

What I have noticed is that in the poetry of younger authors, you have this offshoot of coming up against the conservative society that seems to be in the cultural memory of Latgale and what you are expected to do as a good member of society – getting married and having kids young, going to church, things of the sort – and this new poetry either tries to fight this way of thinking, or goes off in a completely new direction style-wise. Perhaps it’s fair to say that it isn’t as if there are hundreds of authors coming out with work every year, but I think what is being published really has something to say to a wider readership. It’s universal, but also shows the color of the region. For example, Ligija has a poem in The Last Model where she talks about Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius and using Cyrillic, which is a nod to the rather large minority of Orthodox believers in the region. I don’t seem this imagery often in Baltic poetry, so there are certainly surprises to be had in Latgalian literature.

Is there any exciting translation project you’ve got coming up or coming out you’d like to share?

After a rather busy last few years, I decided to take a short break, do some shorter-term projects, and gather up my energy for something new. Translation is tough, if you are putting the work in. It’s a physical job, strangely enough, not just mental, and at some point you need to step back, take a look around, and do other things. It’s a healthy breather. I think jobs where there is no exact linear path are like that. There is no template for literary translation – you have to learn to ride the wave and then sometimes just be on the beach and enjoy watching the water shimmer.

Read Jayde Will’s translations of Latgalian and Latvian poetry, and more, in the upcoming issue of Panel Magazine issue 7, coming out 25 June 2021.

Photo of Jayde Will by Inga Pizane

Leave a Reply