Reading Magda Szabó in English

Jennifer Walker

As dusk set in on a December evening on Júlia utca in Budapest’s Pasarét neighbourhood, under the shadows of the three storey apartment blocks, a grey and white cat shaped like a barrel waddled towards us. The chubby cat rolled on her back and purred as she let me pet her tummy. Any cat lover will tell you that giving a cat a belly rub without the claws coming out is a rare moment, but this time it was even more special. Not only was this a cat I had just met, but we came across the cat on a poetic moment of a literary pilgrimage I made with my Hungarian mother to the former apartment of her favourite author.

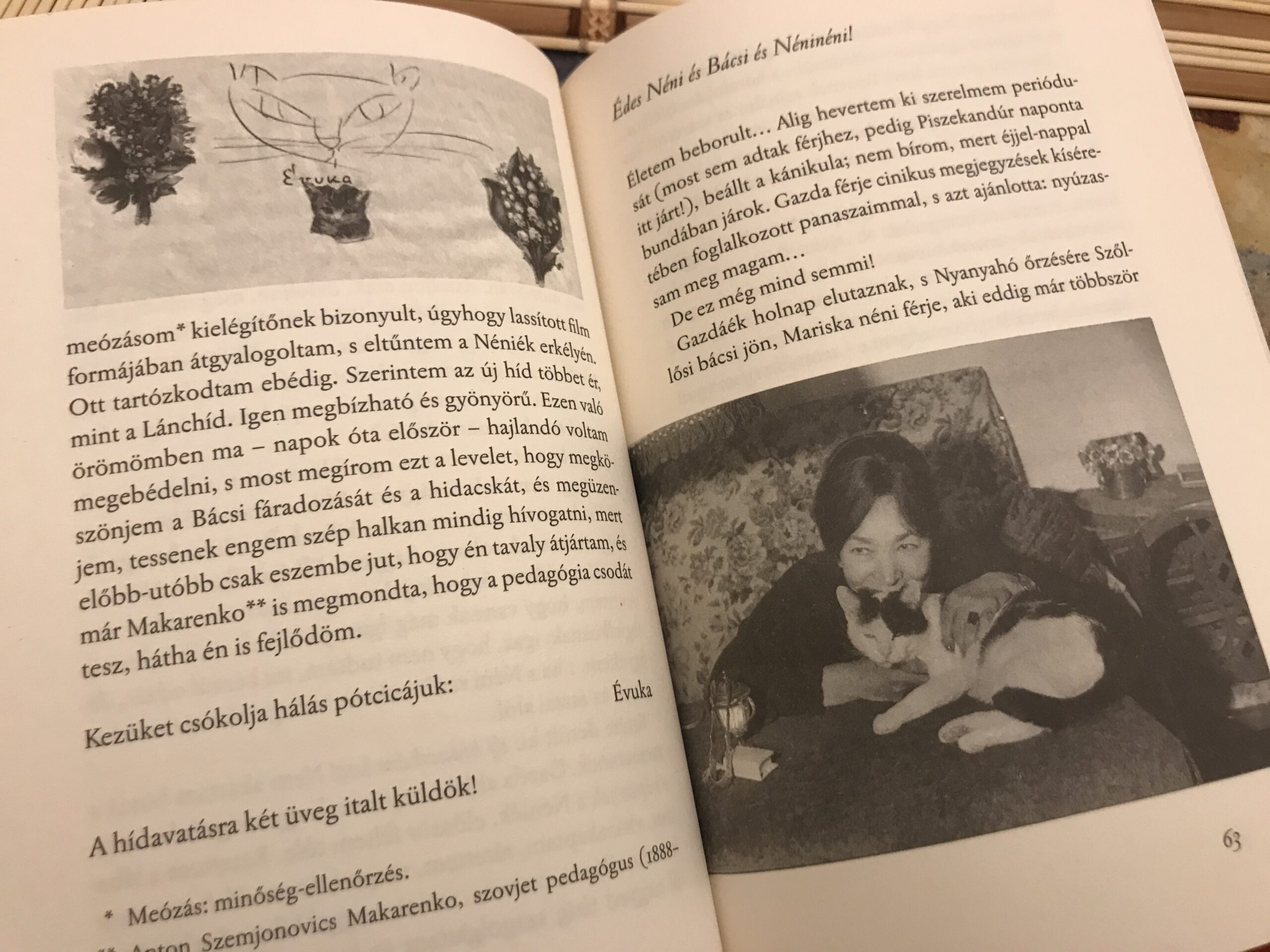

From the outside, there is nothing special about Magda Szabó’s apartment, going up the street lined with bare chestnut trees and dried ivy, we missed it the first time as we looked for the building in the fading winter light. The cat appeared besides the railing, squeezing through the bars and leading us along to number three, the house we were looking for, before she rolled on her back and submitted to being admired. We noticed the flirty feline first before the house number, but it captured the spirit of Magda Szabó, as the author loved cats. You’ll see many photos of the author featuring a plump black and white cat sitting proudly on her lap or a rotund tabby posed regally beside her typewriter, so it felt natural to stroke one right outside what was once her front door.

It was my mother’s idea to go to Pasarét. One of our bookshelves at home has an entire row dedicated to Magda Szabó’s books. My mother has often recounted their synopses to me in English and in great detail, and gave me a translated copy of Katalin street for Christmas last year. I had all these stories yearning to be read in my living room, but I was not confident enough to read them in their original Hungarian until lockdown this spring. Abigail had just come out translated into English, but my mother handed me her Hungarian copy and assured me it wasn’t a difficult read.

It took me more than a month to read it in Hungarian. Still, despite the complexity of Szabó’s stories and the human nuances I’ve appreciated in the translated versions, I was surprised to find the Hungarian prose simple enough for me to follow with my child-like Hungarian (at least in Abigél, which falls close to a young adult book compared than her others). It has opened the door to her other books on our bookshelf, but it made me realize the importance of literature in translation and how they function as a gatekeeper to a country’s literary scene.

Although Szabó lived and wrote in the mid and late 20th century (she died in 2007), her work has only begun to gain international recognition since her 1987 novel The Door was available in English. Stefan Draughton translated The Door in 1995, but it was Len Rix’s 2005 translation that gave the book the spotlight it deserved, especially the 2015 edition that made the New York Times Book Review Top 10 list. Despite having had a couple of books translated in the 1960s (which are unavailable today), Szabó’s work came to the international spotlight in the 21st century, and today she is the most translated Hungarian author with publications in over 40 countries and 30 languages.

Szabó’s body of work is extensive and eclectic, some books chronicling her family history back in 19th century Debrecen, to memoirs of her time spent in Vienna and books about her beloved cats. However, it’s her novels that people know and love her for, and while I hope and expect more and more of her exquisite work becomes accessible to the English market, here are a few books to get started with if you’d love to delve into Madga Szabó’s books.

The Door (Az ajtó)

The Door (Az ajtó)

The Door is Magda Szabó’s most iconic work.

Although the point of view character is called Magda and uncannily resembles the author—she lives with her husband who is also a writer, both of whom had their work banned by the communist regime, much like Magda Szabó and her husband Tibor Szobotka—, the book is considered fiction and not a memoir. It explores the relationship between a young writer and her eccentric and mysterious housekeeper Emerence.

Emerence is proud and incredibly private, as no one is permitted past her front door. Magda unveils Emerence’s secrets bit by bit as the two women grow closer. It’s a powerful, poignant novel, and one that will leave you shaken up after reading it. Take time to read it and reflect on it.

Abigail (Abigél)

Translated by Len Rix

In the backdrop of World War II, Gina Vitay, a spoiled daughter of a Budapest general, is shipped off to a fortress-like school in the fictionalized town of Arkód on the Great Plains. Cut off from the outside world, Gina rebels against her new surroundings until her father reveals she’s been placed in the school for her safety. Soon Gina throws off her prejudices for the school traditions: Including asking for help from a statue in the garden called Abigail. Letters are thrown into the stone basket and as if by magic Abigail responds and helps the girls with their problems, no matter how grave or trivial. Hints of war trickle in as the book goes on, and the tension and adventure ramp up. I don’t want to give away too much from the plot, but if you’re looking for an exciting read, Abigail won’t disappoint.

Katalin Street (Katalin utca)

Katalin Street (Katalin utca)

Translated by Len Rix

Katalin street is a tale not only about a group of families living next door to each other on a fictionalized road in Buda, close to the Danube River, but is a story about Hungary through the regimes of the 20th century and how our past haunts our present. Four childhood friends, Bálint, Irén, Blanka and Henriette, live a happy life before the war. Still, in 1944 with the German occupation, the characters’ lives are torn apart, as the deportation of the Jewish Held family and the tragic death of their daughter Henriette, haunt Bálint, Irén and Blanka into their adult lives. After the war, the families from Katalin street are moved into cramped communist apartment blocks and are forced to recall their past. Katalin street carries curious elements of Magical Realism, which gives the novel a curious edge, and like Szabó’s other books, is both harrowing in parts and beautiful at the same time.

Iza’s Ballad (Pilátus)

Translated by George Szirtes

Iza’s Ballad carries echoes from The Door in that we have a story threaded around two women exploring each other’s world, except in this case they are mother and daughter. When Ettie’s husband dies, her daughter Iza brings her up from the countryside to live with her in Budapest. Ettie struggles to adapt to city life, committing faux pas such as inviting a prostitute for tea. Iza’s Ballad is kind of a slow burner compared to Szabó’s other books, but once the story gets going, its a moving, human account of a mother and daughter who are not only strangers but two women who struggle to know and understand each other, as they appear to come from entirely different worlds.

Leave a Reply